The Economist Magazine’s Graphic Detail column recently reported on military spending across countries for 2023, based on SIPRI’s measures of defence spending and this sites military PPP data.

This week the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) also released a new report commenting on significant military spending of some NATO countries, such as Poland, when viewed in military purchasing power terms.

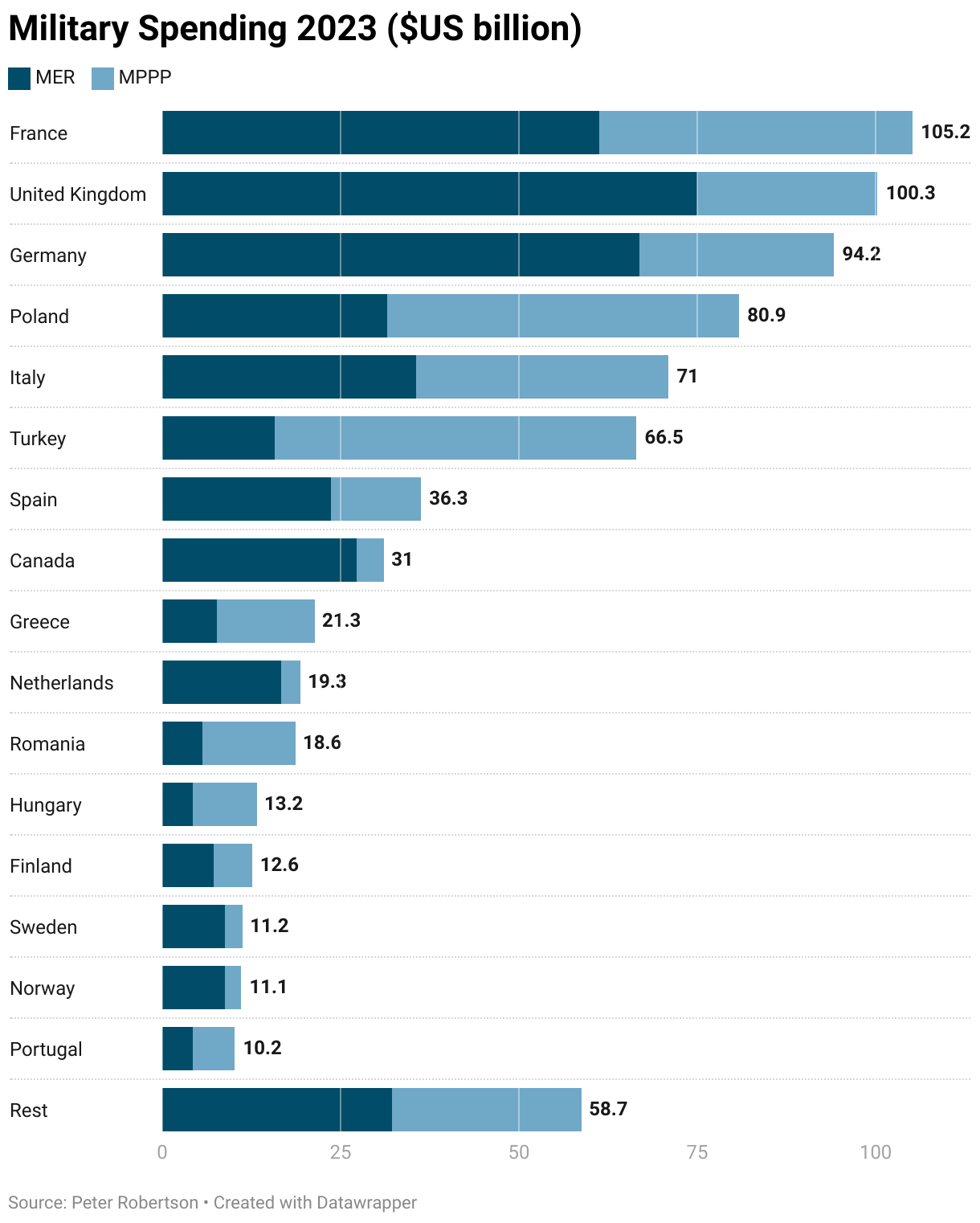

The graph below highlights these points, and shows the difference between NATO’s military spending when measured at market exchange rates and when measured at military PPP exchange rates. The difference is large and affects the way we might think about the relative contributions of NATO members.

In market exchange rate terms the rest of NATO spends $US 0.43 trillion. But in real (military PPP) terms this has the purchasing power equivalent of $US 0.76 trillion, comparable to the USA’s $US 0.93 trillion defense budget.

This should not be surprising if, as some contend, the the Euro has been undervalued by as much as 20% relative to the US Dollar. An overvalued dollar or, equivalently, weak Euro will tend to make European NATOs military spending seem small relative to the USA when converted to dollars at market exchange rates.

In addition, however, labour costs and other prices also vary significantly between European NATO countries. For example Turkey has a large military but comparatively low wages, meaning that a dollar of spending on personnel goes further in Turkey than it does in Germany or the UK.

To get a better understanding of the how different countries contribute to NATO in real terms we can look at spending in each country.

Turkey, Poland and Italy all have large armed forces and relatively low wages and contribute substantially to the overall large PPP adjustment for European NATO. Interestingly France also has relatively low unit personnel cost compared to Germany and the UK and so there is a relatively large PPP adjustment for France also.

This means that for Turkey, Poland, Italy, Spain, but also France, the real size of the armed forces is likely to be significantly understated when market exchange rates are used to compare military spending across countries. Similarly Romania Greece and many smaller countries, have larger armed forces than suggested by market exchange rates.

This metric doesn’t affect measures of burden sharing, which only depend on costs in local currency. But it does suggest a different perspective on what each country might bring to the table – which can be more than the usual market exchange comparisons suggest.

Note that the Rest of NATO in the preceding Figure consists of Denmark, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Slovak Republic, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia. Together they are significant contribute almost as much as than Turkey. The main difference in these estimates is due to lower labour costs in these countries.1

For data updates please subscribe.

- The usual caveats apply with respect to data quality, estimates of budget shares and labour quality adjustments. Moreover all measures of military spending, whether at market exchange rates or adjusted for purchasing power, are only measures of inputs, not outputs, military power or military capacity. Also data are also preliminary. They are estimates, based on 2022 and 2021 values since as some of the key variables used to compute PPP adjustments are not yet released, particularly World Bank GDP-PPP estimates for 2023. Nevertheless they will give a reasonable approximation. ↩︎